COMPETITIVE GOVERNANCE

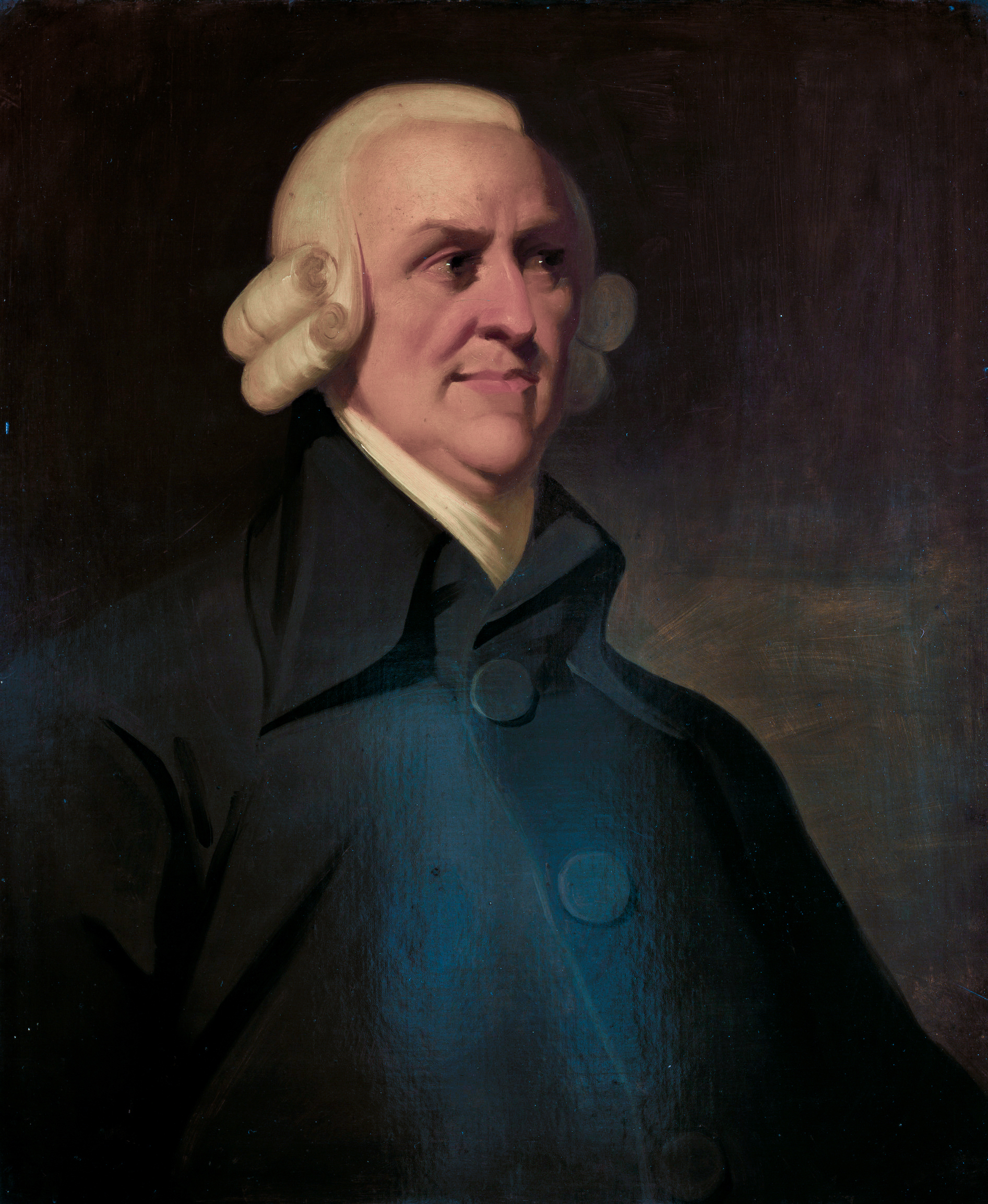

In his magnum opus, “An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations”, Adam Smith recognizes free markets as an incentive alignment device:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.

Proponents of classical free-market economic theory have long extolled the virtues of using strong economic incentives to channel self-interest towards socially desirable ends. Unfortunately, however, the role of free markets in facilitating a credible threat of exit and establishing mechanisms of institutional evolution across jurisdictions has largely been unexplored. In this post, I examine those characteristics of the free market and posit that faciliating jurisdictional competition can combat many of the challenges and inequities plaguing societies around the world.

Hyperpartisan politics

In “Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life”, Nassim Taleb argues that having a measurable risk when taking major decisions functions as a Darwinian filter that balances both incentives and disincentives: an actor who benefits if something for which they are responsible goes right must also bear the costs should it go wrong. For example, participants in competitive labor markets such as hedge funds have "skin in the game" because most owner-operators have at least half of their net worth in the funds, making them relatively more exposed than any of their limited partners. Hence, the hedge fund industry has experienced continuous evolution, where the worst-performing hedge funds go bust and exit the system.

On the contrary, elected political officials lack "skin in the game" because they do not bear direct costs from their decisions. While free and fair elections serve as instruments of accountability, officials in the electoral market exploit partisanship to keep a hold on the reins of power despite performing abysmally. This is especially true in polarized political oligopolies, where candidates from a limited number of parties offer a bundle of ideological positions that are often inherently uncorrelated. For example, consider a political party whose manifesto could be modeled by an n-dimensional vector, where the “i-th” element corresponds to the official party position on policy “i”, which could be firearms laws, tax rates, and so on. A politician operating in an oligopoly could offset lackluster performance on policy “i” by delivering on a less important policy “j”, albeit one which rouses its most ardent supporters, thereby putting them in a strong position to get reelected. This not only undermines the spirit of democracy but also creates perverse incentives where elected officials only pursue reforms, regulatory or otherwise, that are relatively easy to achieve politically.

There seem to be two ways to escape an hyperpartisan political milieu:

1. Reduce the number of dimensions offered in an ideological bundle: The electorate could "apoliticize" certain policies currently on the ballot, thereby reducing the number of ideological positions candidates have to hold. Disciplining political candidates to exclusively bear on a small set of concerns faciliates a marketplace of ideas, where politicans are voted based on explicit policies, rather than as symbols for abstract ideas. For instance, consider the case where politicians only focus on improving overall standards of living for everyone and maintaining the rule of law, without concerning themselves with regulating societal mores. In this event, one could even use metrics on the political landscape. Competing political candidates could rally voters by proposing to increase the GDP per capita by “x%” and underlying the steps they would undertake to do so. Furthermore, failure to deliver on the promised metrics could automatically disqualify them from contesting for reelection.

2. Increase the number of political parties: It is certainly possible that a candidate has a subset of policies that are appealing to a specific segment of the electorate, while they simultaneously have another subset of policies that are not appealing in the least to the same segment of the electorate. In this event, voters would weigh their priorities, often finding themselves holding their noses while they cast their votes. This condition arises when the number of ideological positions up for discussion in the political arena exceeds the square of the number of political parties. For instance, consider the case where there are a total of n2 parties. In this event, every combination of ideological positions would be represented at the ballot, leading to an electoral outcome that is a more accurate reflection of the electorate's preferences.

A third way?

In “Exit, Voice, and Loyalty”, political scientist Albert Hirschman laid out a model to explain relationships between an organization, whether a business, a nation or any other form of human grouping and its members. The basic concept is that an individual has two possible responses when they perceive a deterioration in the quality of goods provided by the organization: they can withdraw from the relationship, i.e. exit, or they can attempt to improve the quality of goods through a proposal for change, i.e. voice. For example, disgruntled employees can either choose to quit their unpleasant job, or express their concerns in an effort to improve the situation. While it is certainly evident that emigration is an instantiation of Hirschman’s scheme of exit, the absence of a market for citizenship has failed to facilitate an improvement in the quality of governance over time. An evolutionary approach to competition among governments promises to foster institutional innovation.

The quality of governance could be improved by subjecting political systems to market forces and disciplining elected officials to optimize value creation as opposed to optics. One such proposal is the Charter Cities Institute, a nonprofit promoting the creation of new cities as a revolutionary solution to lowering the barriers to entry for governance ideas. The creation of new special jurisdictions would increase competitive pressures on governments to adopt reforms that alleviate poverty and promote capital-friendly policies. Eventually, a highly liquid market for nation-states could emerge, leading to a condition known as Tiebout sorting, the sorting of individuals into communities that best suit their needs. For example, consider an individual whose political preference can be modeled by an n-dimensional vector. Then, Tiebout sorting would lead to a condition where this vector of preferences is not merely treated as something that has to be aggregated, but rather as a query into a search function. The search results would rank order all jurisdictions in the world that match this particular set of beliefs. Establishing a more credible threat of exit provides a plausible mechanism of improving the quality of governance worldwide.